Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.

~ Charles T. Munger 1924-2023

Charlie Munger passed away late last year at 99 in Santa Barbara, California. Munger was best known as the Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett’s business partner. Sometimes called the “Oracle of Pasadena” (Buffett’s nickname is “Oracle of Omaha”), Munger was known for imparting a good deal of business and investing wisdom in his century of experience, but his quote about incentives is the one that comes to mind for me almost daily.

About the same time Mr. Munger was passing into the next realm, I bought a new Jeep to replace one of our older jalopies soon to be passing into the hands of one of my kids. I’m new to Jeep culture and not particularly brand loyal with utilitarian tools like automobiles (brand affinity being a Missionary trait). My stronger pragmatist wants the most utility for the lowest cost and I’d been watching the days’ supply of 4X4 trucks on Midwest dealer lots (my Mercenary’s key metric for when to strike with a purchase like this) and Jeep’s Gladiator light pickup was the slowest selling car in America at the time.

As my erstwhile teenage drivers were heading back to school this week from the holiday break, the incentive to get some experience behind the wheel of the new ride helped me ensure an on-time departure each morning with the simplest of incentives imaginable: first one to the Jeep rides shotgun.

We left five minutes early.

And that’s the topic of my essay this month: the evolving incentives in our banking sector and an exploration of how those incentives will be even more seriously warped heading into this election year. Things are so out of sync with reality, your B.S. detector is going to need recalibrating. Particularly in the American banking sector systemic changes are continuing to accelerate, which is where I’ll focus below. So come along and let me explain what really happened in 2023 and a peek at what to expect in the year ahead.

Beginning last March with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), followed quickly by Signature Bank’s liquidity crisis, the Federal Reserve suddenly discovered the true cost of their post-pandemic policy actions. After the Board of Governors’ Open Market Committee raised the fed funds rate an unprecedented 11 times over the past 18 months – more than 500 basis points – in December, the worst inflationary cycle in 40+ years seemed to level off, allowing them to signal “higher for longer” might have been more bark than bite.

Of course, when you’re a billionaire VC with a few hundred million on deposit with SVB or Signature paying you a quarter percent yield, you’d be an idiot not to move that capital into money market funds for a better return. Which, they did… and more quickly than anyone imagined. Never before have we had the ability of even the retail banking customer to move money between financial institutions with a few finger strokes of an app on their phone. In the space of weeks, hundreds of billions in fractional reserve asset deposits moved out of savings and checking accounts to higher yielding money markets, including the new ability to buy their own I-bonds or T-bills on TreasuryDirect and get an instant 5% jump in your money’s yield.

We haven’t seen much off this new fangled digital bank run (yet) – it used to be depositors had to turn up at the teller’s window to demand their money, which in a fractional reserve banking system, means there’ll never be enough to go around. The liquidity crisis a bank run creates means a bank can only pay out to depositors if it sells non-cash assets at market, not face, value.

Last March, the phenomenon of Fed interest rate manipulation had metastasized into a full-blown banking sector meltdown. When yields on debt go up, the price of that paper goes down, so all those assets on bank balance sheets had taken a ~50% haircut in face value over the span of interest rate increases – particularly commercial real estate, much of it rotting vacant in American cities as workers continued to WFH post-pandemic. To make matters worse, commercial real estate financing isn’t like buying a house with a locked-in, predictable 30-year mortgage; commercial/office debt revolves on a refinancing schedule more like five years, so a lot of the bank assets tied up in commercial real estate debt refinanced just before COVID-19 will be refinancing in 2024-25.

Maybe you watched Frank Capra’s 1946 Christmas classic about the Great Depression, It’s A Wonderful Life over the holidays? I did. And dang it if every time Miss Davis asks for $17.50 I still don’t burst into tears!

Don’t Call It A Bail-Out

When SVB halted withdrawals, the writing was on the wall and the Fed swung into action to avoid another high profile taxpayer bail-out with a new lending facility from the Discount Window called the BTFP.

Incidentally, bank bail-outs don’t happen any more because bail-outs are no longer strictly legal. After the GFC nearly ended our debt-based monetary system in 2008, politicians and bureaucrats alike realized just how badly things looked to voters when Wall Street “banksters” get taxpayer money to reliquefy their sketchy loan and investment portfolios simply because they’re systemically important. Fifteen years ago it was the sub-prime mortgage market that triggered the meltdown. Now, the Fed is worried it’d be commercial real estate refinancing. In the carefully scripted words of a man who would know – Mr. Richard Ostrander, the General Counsel of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, here’s what happened:

Over the weekend of March 11 and 12, the Fed designed the BTFP to support the stability of the broader financial system by providing a source of financing for banks with Treasury, Agency and other eligible holdings whose market value had significantly diminished given interest rate increases. Market participants were very focused at the time on banks with large, unrealized losses in their holdings of these sorts of securities. The rapid deposit growth of both SVB and Signature in the wake of the pandemic resulted in these banks holding quite large Treasury and Agency positions relative to their overall balance sheet. Where a bank is holding securities on its books as “held to maturity”, changes in market value do not affect book equity or regulatory capital.2 However, the unrealized losses may—and in recent cases, did—affect the ability of the bank to sell or pledge those securities to generate liquidity. Selling these securities, as we saw with SVB, creates a realized loss on the balance sheet. Borrowing against the securities would not have forced the bank to realize a loss, but the value of these securities as collateral would have been calculated using market value, not face value. Accordingly, these securities may not have generated as much liquidity as the bank needed, desired, or anticipated. BTFP was an innovative way to create an additional source of liquidity using these high-quality securities, calming market fears over the consequences of fire sales.3

The Bank Term Funding Program was designed over a weekend (in case Monday needed to be an impromptu “bank holiday”… a possibility we’ll revisit later), and just like that the Fed saved the banking system from a digital run that would’ve reshaped life as we know it. And not just for Americans – this is a global banking system with counter-party risk assets and liabilities estimated at greater than US$ 2 quadrillion held by investors worldwide, so a liquidity crisis in the U.S. is an even bigger surprise to European and Asian banking partners.

The Biden Administration was quick to assuage any fears of systemic instability:

“Americans can have confidence that the banking system is safe,” Biden said at the White House. “Your deposits will be there when you need them.”

Biden said ”no losses” from the collapse would be borne by taxpayers, and the money would come from the fees banks pay into the Deposit Insurance Fund.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC, took control last week of SVB’s assets after the bank ran out of cash. Federal regulators also assessed over the weekend that Signature Bank of New York presents a systemic risk and took it over. Biden said Monday that managers of the banks would be fired and investors would not be protected.

Customers of the banks, including small businesses that need to make payroll, would have immediate access to their money, the president said.

Let’s hop back to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s General Counsel for some color on this “banking system is safe” headline.

BTFP loans are recourse to the borrowers, so the lending reserve bank is not limited to just looking to the BTFP collateral for repayment in the event of a default. Instead, the reserve bank would have a claim for repayment in full against the borrower. After applying BTFP collateral, the lending reserve bank may also recover against other assets, if any, pledged in connection with regular discount window arrangements or otherwise.8 If this additional collateral is inadequate and the borrower cannot otherwise repay the BTFP loan, the Treasury Department has agreed to reimburse the Federal Reserve for aggregate losses on BTFP loans up to $25 billion.9

As I previously mentioned, the U.S. banking sector stabilized thanks, in part, to the BTFP assuring markets that banks with underwater government securities portfolios can use those to generate liquidity on the basis of their par value. It helped avoid a fire sale. As of May 31, the total outstanding amount of advances under the Program was approximately $107 billion, while the collateral pledged to secure the loans was approximately $129 billion.10

No taxpayer funds bailed out nobody, thank you very much! The Treasury is on the hook for any losses over $25B and we’ve got a collateral spread of $22B – the banking system is fine.

So where do we go from here? The banking system is sound, your money is safe, inflation is under control, right? Well, as old Charlie Munger might ask, if we haven’t changed the incentives can we expect any changes to future results? What will I be personally doing to safeguard any scenarios where Treasury and the Fed don’t feel obligated to intervene to backstop the banking system on my behalf?

Back in 2010 the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act dealt with banking reform – specifically the “too big to fail” banks who got bailed out by taxpayers – in Title II: Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA). Among other things meant to prevent future bank bailouts, OLA created a process (known as a “bail-in”) to liquidate financial institutions without taxpayers footing the bill. Bail-ins cancel a failing bank’s debt owed to creditors and depositors – here’s how it would work:

A bail-in can take place in the U.S. if the Secretary of the Treasury determines that the bank meets the conditions of a two-part test:

- The bank is in default, or in danger of default. A bank is in danger of default when it is likely to file for bankruptcy, has debt that will deplete all or most of its capital, has greater debts than assets, or will likely be unable to pay its debts in the normal course of business.

- The bank represents a systemic risk to the banking sector. The likelihood of systemic risk is based on the negative effect of default on financial stability; low income, minority, or underserved communities; and on creditors, shareholders, and counter-parties.

If, as a result of the evaluation, the Secretary and/or the bank’s board of governors believe the bank is a candidate for a bail-in, the board will vote on providing a written recommendation to the Secretary for the FDIC to be appointed receiver of the bank.

So, as long as you – the retail bank customer – don’t have deposits exceeding the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit per account you wouldn’t face any uninsured losses. No problem right? Who’s sitting on that kind of cash hoard in this economy anyway?! The median value of U.S. individual bank transaction accounts (checking, savings, money market accounts) was $5,300 in 2019, the last year we have data for.

So why didn’t Janet Yellen, Biden’s Treasury Secretary, force a bail-in with SVB? It wasn’t the fat cat bankers getting bailed out. It was the much more politically active fat cat VCs with accounts in the hundreds of millions and billions, far beyond the FDIC’s $250K limit, who were backstopped this time. These aren’t little people like you and me with our lousy 5,900 bucks – almost 94% of SVBs deposits were uninsured… and SVB’s depositors aren’t the only ones with risks outkicking their coverage, as my brother likes to say.

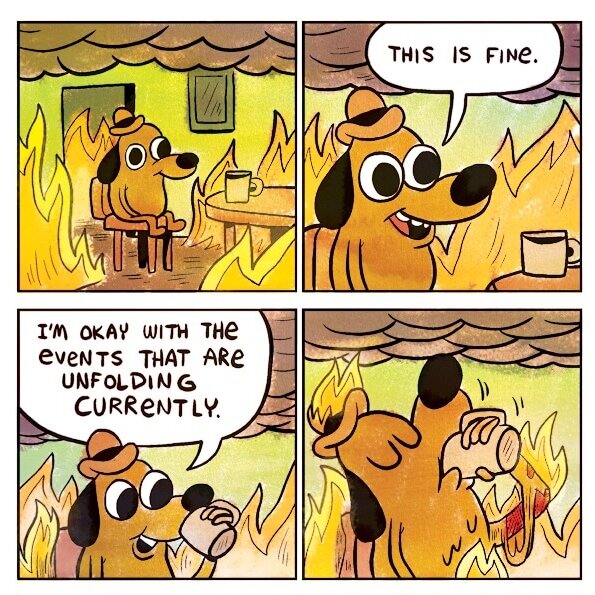

A chart like that starts a guy thinking. Signature Bank was next to go, just two days after SVB, then seven weeks later, First Republic – three of the four largest bank failures in U.S. history happened in less than eight weeks. But the banking system is safe. Everything is fine.

Although a U.S. bail-in has never happened, SVB’s bail-in would have been extremely problematic, especially the year before national elections. I’m not political, but something tells me if the depositors were just a little less personally connected to powerful elites, SVB might’ve been America’s first example. The only real idea of how a bail-in might unfold is Cyprus, where the government forced a banking system bail-in in 2013 after the Cypriot banking sector was at risk of insolvency due to bad loans and risky investments going bust. Sound familiar? Depositors with more than 100,000 euros were forced to write off 47.5% of their bank holdings, preventing bank failures, but causing fresh anxiety among investors nervous bail-in write-downs would become more common.

What’s going to happen with the U.S. banking sector in 2024? Of all the scenarios I’m interpreting privately, the most curious asks a provocative question: if we’re in a cashless society, who needs a bank? The actions I’m taking based on other, less obvious questions you’ll have to read about at our website. If you haven’t heard, unpopular opinions are forbidden on the Internet lately – that smart mouth of yours can get you canceled.

However, I will share one expectation I have coming back into vogue in months ahead: the resurrection of the Chief Risk Officer to lead macro risk management. Back to Mr. Ostrander for the dismount on this idea, which, he suggests we need to balance our perspectives on growth and risk:

Within SVB, for example, I wonder, who was asking the tough questions? Who was challenging decisions about the bank’s balance sheet and interest rate risk—in particular, its reliance on large, uninsured deposits and the ballooning of longer-duration investment securities as a percentage of its total assets—and asking, candidly, can this hurt us? If so, how much? And how can we fix it?

This is, perhaps, where the lack of a chief risk officer translated into a real, negative impact on the bank. Though SVB had a risk function, it was headed in the absence of a chief risk officer by the chief executive officer. That does not strike me as an effective way to challenge the risks undertaken to promote growth, since growing a business is a chief executive’s job.

That sounds a little like what happened in the aftermath of the GFC, doesn’t it? It seemed like Chief Risk Officers were trending in every sector back then, but I haven’t heard of it much lately. Hmm. Seems like having somebody watching for the black swans nobody expects will upset our growth plans became a necessary control on strategic overreach. I’ll predict we’ll be needing those controls again in the future. Particularly as we seem to have a more cashless economy, with a regulator as the only check on the macro risks inevitably arising in the market segments banks are choosing to play in.

More importantly is asking what YOU can DO about it, as I have been. But you’ll have to register at our learning community RECONVERGE to be notified when part two of this essay is published in a few days. Register for anything and you’ll be on the list – my brother Derek is hosting his monthly webinar next week in fact, so join us for that if you can.